As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

The 1957 incident at Edwards Air Force Base (Edwards AFB) remains one of the most discussed unidentified aerial phenomena linked to astronaut Gordon Cooper. This account provides historical context, technical specifics about the camera systems in use, an outline of the reported chain of custody for the film, comparisons with contemporaneous military sightings, and a balanced review of skeptical interpretations.

Background: Gordon Cooper’s Role at Edwards AFB

At the time, Cooper was a United States Air Force officer assigned to the high-desert test ranges surrounding Edwards AFB, home of the Air Force Test Center. He served as a test pilot and project manager, roles that demanded precise documentation of flight activities, including calibrated photography used for performance analysis and safety reviews. Cooper later became one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts, which added public interest to any account associated with his name. His later public statements—most notably in interviews and in his memoir—have been central to keeping the 1957 case in the public eye.

The Reported Incident: May 3, 1957

Technical Setup

Cooper oversaw a precision photography project that involved a camera crew assigned to record test aircraft maneuvering over a dry lakebed. Contemporary accounts reference the use of a cinetheodolite system—a specialized optical instrument capable of tracking flight paths at measured frame rates for engineering analysis. The worksite was a dry lake area commonly used for landings and ground-effect testing, where visibility is generally excellent and foreground distance cues are reliable.

The Observation

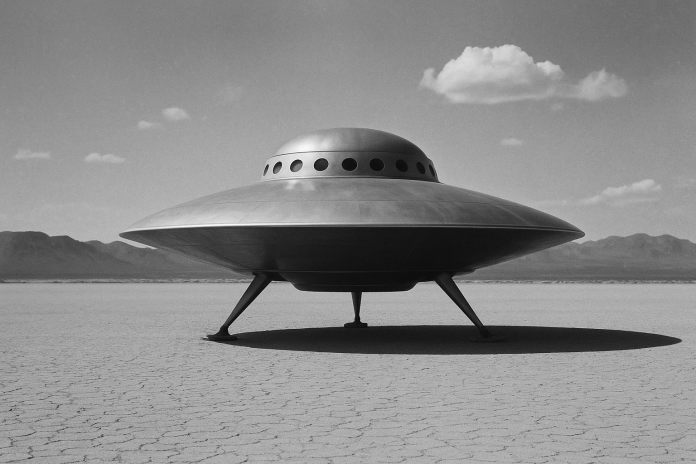

According to Cooper’s later retelling, members of the camera crew entered his office in a distressed state and reported that a silent, saucer-shaped craft descended to the lakebed. They stated that the object extended three landing supports, settled on the surface for a brief period, and lifted off without any audible propulsion signature as they approached to film it. The crew indicated that they captured still images and motion-picture footage of the approach, landing, and departure sequence.

- Reported geometry: “saucer-shaped” planform with three extended landing legs

- Acoustic profile: described as silent during descent, hover, landing, and liftoff

- Distance and perspective: sighted at close range on a flat lakebed with clear lines of sight

- Recording media: still photography and motion-picture film reportedly exposed

Aftermath and Film Handling

Cooper later stated that he followed standard protocols by contacting a designated number and arranging for the film to be processed and delivered to higher headquarters in Washington, D.C. He said he viewed the developed material prior to forwarding it and believed it matched the crew’s description. Cooper also said he did not receive formal feedback after the material left the base. Readers should note that while such a chain-of-custody narrative is consistent with Cold War–era handling of sensitive imagery, the lack of a publicly accessible archival record leaves the evidentiary trail incomplete. For background on the period’s official studies, see Project Blue Book.

Edwards AFB in Context

Edwards AFB served as the epicenter of postwar American flight testing. The high desert provided controlled airspace, expansive landing areas, predictable weather, and the infrastructure needed for advanced aeronautical research. Test pilots and engineers at the site worked on cutting-edge platforms and systems under strict security, which heightened both the plausibility of unusual observations and the possibility of misidentifications. The base’s reputation as a hub for experimentation is well documented in resources about the Air Force Test Center and U.S. military aviation history.

Technical Notes on Cinetheodolites and Instrumented Filming

A cinetheodolite is engineered to measure angular positions of a target while simultaneously recording imagery at a known frame rate. When paired with a second synchronized unit across the field, analysts can reconstruct trajectories through photogrammetry, calculate angular rates, and estimate velocities and altitudes. These instruments were common at military ranges during missile tests and high-speed aircraft trials. Their use at dry lakebeds offered a robust method for collecting kinematic data, assuming calibration logs and timing data are preserved—elements that, in this case, have not surfaced in the public domain.

Summary of Reported Key Details

| Detail | Description |

|---|---|

| Date | May 3, 1957 |

| Location | Edwards Air Force Base, California |

| Camera System | Askania-type cinetheodolite (range instrumentation), fixed frame rate |

| Camera Crew | Two range photographers (names have been reported in secondary accounts) |

| Object Description | Disc-like craft; three extended landing legs; low-altitude hover; silent landing and liftoff |

| Evidence | Still and motion-picture film reportedly exposed; transferred under order to higher headquarters |

| Follow-Up | No public documentation of analysis; no official release of film; potential relevance to Project Blue Book |

| Public Visibility | Incident persisted through media interviews, Cooper’s later statements, and documentary treatments |

Comparisons with Contemporary Military-UFO Film Cases

Placing the Edwards report alongside earlier filmed cases is helpful for context. Investigations during the early 1950s included incidents where motion-picture cameras captured unusual objects, and analysts attempted to assess size, speed, and flight behavior from imagery. Two notable examples that entered the public record are frequently cited in historical surveys of U.S. UFO research.

- Great Falls, Montana (1950): Often called the “Mariana UFO Incident,” the footage was shot near a minor-league baseball park. Subsequent study focused on whether the objects were aircraft or reflections. See Great Falls UFO incident.

- Tremonton, Utah (1952): A Navy chief petty officer filmed a cluster of bright objects. The Robertson Panel reviewed this case and considered potential conventional explanations such as birds or balloons. See Tremonton UFO film.

In both examples, analysts grappled with the common limitations of mid-century film: exposure, focus, lens flare, and scale ambiguity without range data. Range instrumentation—like synchronized cinetheodolites—could reduce uncertainty if baseline distances, timing, and calibration records were preserved. The Edwards account’s persuasiveness rests on the assertion that calibrated equipment captured close-range imagery at a test range; the absence of publicly released frames or logs keeps the case in the category of unverified testimony.

Cooper’s Later Statements, Public Advocacy, and Media

Cooper discussed the 1957 event in interviews and in his memoir, Leap of Faith. He also addressed unidentified aerial phenomena at international venues, including a widely referenced 1978 appearance related to the United Nations. Popular documentaries such as Out of the Blue later amplified his perspective. While these sources contributed to the incident’s visibility, they did not add verifiable photographic evidence or official analytical results to the public record.

Skeptical Interpretations and the Archival Record

Researchers who approach the Edwards account skeptically point to gaps: a missing film record, no accessible chain-of-custody paperwork, and no clear entry in declassified case files attributed to the 1957 date and location. Some media analyses suggest that observers could have encountered a classified test article or misinterpreted conventional stimuli. Others note that Project Sign, Project Grudge, and later Project Blue Book collectively documented many sightings, but that a direct, indexed file matching Cooper’s description has not been demonstrated publicly. For a representative example of a skeptical narrative with regional context, see Courthouse News.

It is reasonable to note that not all materials from Cold War programs were retained, declassified, or cataloged in publicly searchable formats. Conversely, it is also reasonable to expect that a high-quality, close-range film captured with range instrumentation would leave some kind of paper trail. The tension between those two realities sustains ongoing debate about the Edwards case’s evidentiary status.

Methodological Considerations: How Investigators Evaluate Such Claims

When assessing historical accounts that hinge on missing media, investigators typically look for convergence across independent lines of evidence. Items of interest include custody logs, lab processing records, references to frame counts or focal lengths, and corroboration from range safety officers or engineers. Calibrated imagery from a cinetheodolite can be powerful if accompanied by metadata; in the absence of that data, analysts default to qualitative assessment of witness reliability and environmental context. At a site like Edwards AFB, where test activities were sensitive, both extraordinary sightings and heightened secrecy were part of the operating environment.

Why This Case Endures

The Edwards account persists for several reasons. First, the setting—a premier U.S. flight test center—lends weight to any claim arising there. Second, the reported use of range-grade filming equipment suggests that the observation could have been documented with unusual clarity. Third, the principal narrator later became a prominent NASA astronaut, increasing public interest. Finally, the unresolved status of the purported film invites continued inquiry. Each factor keeps the narrative in circulation within discussions of mid-century unidentified aerial phenomena.

Related Programs and Institutional Backdrop

From the late 1940s through the 1960s, the U.S. Air Force organized multiple efforts to log and analyze reports. Project Sign began in 1948, followed by Project Grudge and, ultimately, Project Blue Book, which operated until 1969. In 1953, the Robertson Panel recommended treating the subject with a view toward national security and public education to minimize misinterpretations. That institutional backdrop, coupled with the security culture at test ranges, helps explain how an event with intriguing claims could remain undocumented in public sources while still being plausibly noteworthy to those who were present.

Assessing Competing Hypotheses

Competing explanations for the Edwards account include a misidentified conventional aircraft or test article, a balloon or target drone under unusual lighting conditions, or a classified system unfamiliar to the observers. The “silent” attribute is sometimes cited against conventional aircraft; however, distance, wind direction, and atmospheric conditions can attenuate or mask sound. Conversely, landing on visible legs at close range argues against many prosaic candidates. Without the film, each hypothesis remains provisional. A sound historical approach is to document what is claimed, present the institutional context, and highlight where the record is strong or sparse.

Media Literacy and Source Hierarchies

Readers navigating this topic encounter a spectrum of sources—from memoirs and documentaries to newspaper features and encyclopedic summaries. Works like Out of the Blue helped popularize Cooper’s perspective, while encyclopedic overviews on Gordon Cooper and Project Blue Book supply neutral scaffolding. Regional reporting such as the Courthouse News piece offers local context and skeptical viewpoints. Because first-generation technical artifacts (film frames, calibration records, lab logs) are unavailable, careful readers prioritize transparent sourcing and differentiate between primary testimony and secondary narrative.

What Would Settle the Question

A definitive resolution would require recovery of original film elements or verifiable duplicates, plus any associated range documentation—exposure sheets, camera station logs, synchronization records, and courier paperwork. A credible chain of custody connecting Edwards AFB to a receiving organization, potentially aligned with Project Blue Book timelines, would permit technical reconstruction and independent analysis. In the absence of such material, the case’s status remains an informed historical curiosity—important to the cultural history of flight testing and public interest in unidentified aerial phenomena, yet incomplete as evidence.

Summary

The 1957 Edwards AFB report associated with Gordon Cooper combines a compelling setting, trained observers, and the claim of calibrated film evidence. It sits at the intersection of Cold War secrecy, rigorous range instrumentation, and enduring public curiosity about unidentified aerial phenomena. Context from mid-century military studies—Project Sign, Project Grudge, and Project Blue Book—shows that institutional mechanisms existed to process such material, yet no publicly accessible record has surfaced to settle what was captured that day. As a result, the incident remains an important but unresolved episode in the history of test-range observations, sustained by testimony and secondary accounts, and continuously revisited in research and media discussions.