DNA of The ONLY Clovis Ever Found Changes Everything We Know About The First Americans!

The story begins in the unlikeliest of places — a gravel pit in rural Montana, 1968.

Beneath a cliff face, the Anzick family had permitted workers to dig for construction materials.

It was an ordinary day, until the shovel struck something that wasn’t stone.

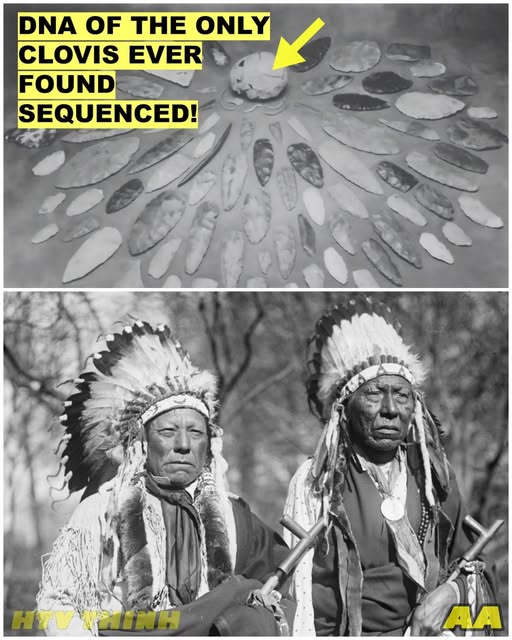

What emerged was both haunting and holy: the fragile remains of a small child, buried with precision, wrapped in a red dusting of ochre, and surrounded by an arsenal of tools carved from ancient stone.

There were spear points, scrapers, blades — more than 125 artifacts in total.

Each one fluted, flaked, and polished with a skill that seemed to defy time.

The tools screamed “Clovis,” but the bones whispered something deeper — something that would take half a century to finally understand.

The child, later named Anzick-1, was no older than 18 months when he died.

His burial was not random.

It was ceremonial — deliberate.

Whoever his people were, they loved him enough to lay him among their finest creations, as if ensuring he carried the essence of their world into the next.

For decades, those bones sat in quiet storage, studied, labeled, forgotten.

But time, like DNA, preserves its own kind of memory.

And in the 2010s, new technology — next-generation DNA sequencing — made it possible to extract and read that memory for the first time.

It wasn’t easy.

The Montana soil had been merciless.

Centuries of freeze and thaw had shredded his DNA into microscopic fragments.

Scientists at Texas A&M and Montana State spent months cleaning, verifying, sequencing.

They tested for contamination, watched for telltale signs of molecular decay — and when they finally saw it, the pattern was unmistakable.

The damage, the chemical scars, the deamination — it was ancient, authentic.

Anzick-1’s DNA was real.

And when they decoded it, the world changed.

The results were shocking in their clarity.

The boy’s maternal lineage — passed from mother to child — belonged to haplogroup D4h3a, a rare branch seen today among Indigenous peoples of the Pacific coast.

But the boy had lived inland, hundreds of miles from any ocean.

That single fact shattered the neat, tidy theory of a purely coastal migration into the Americas.

The paternal story told something just as remarkable.

His Y chromosome, Q-L54, matched one of the founding lineages of Native American men.

Together, they formed a genetic bridge stretching back nearly 17,000 years, to the moment when small bands of humans crossed the ice and tundra of Beringia, leaving Asia behind forever.

But Anzick-1’s DNA revealed something even more profound.

He wasn’t just related to modern Native Americans — he was their ancestor.

Genetic comparisons showed that up to 80% of today’s Indigenous peoples in Central and South America share ancestry directly with him.

The child from Montana had descendants stretching from the Maya jungles to the forests of Brazil.

His genome was the blueprint of a continent.

And yet, not everyone fit that pattern.

About 20% of Native American DNA did not trace through him — a quiet clue hinting that the Americas’ first chapters were written by more than one group.

Somewhere out there in the prehistoric dark, another lineage had crossed the ice, settled, and thrived — and we have yet to find them.

For archaeologists, it was both vindication and revolution.

The Clovis people, long cast as North America’s “first,” were no longer a mystery tribe who vanished without a trace.

Their blood still flowed, alive in millions.

But the findings also deepened the mystery.

The Anzick genome revealed a split — a branching of two ancient American lineages before the Clovis era even began.

Northern tribes like the Cree and Ojibwa descended from an older divergence, while southern peoples shared the Clovis boy’s line.

This meant that by the time the Clovis culture blossomed 13,000 years ago, America was already a patchwork of genetic identities.

It also ended one of archaeology’s most controversial theories: the Solutrean hypothesis.

Some had claimed that the Clovis descended from Paleolithic Europeans who crossed the Atlantic during the Ice Age.

But when scientists compared Anzick-1’s genome with ancient European DNA, they found nothing — no match, no link, no trace.

Instead, the boy’s closest relatives were in Siberia, particularly a 24,000-year-old skeleton from the site of Malta, near Lake Baikal.

The Clovis, it turned out, were sons of Asia, not Europe.

The first Americans were born from the ice and wind of the north, not from Atlantic wanderers.

And yet, the discovery came with a human cost.

Once scientists confirmed the child’s Native ancestry, ethical questions loomed.

The remains were not just data points — they were a person.

A child.

A relative.

Indigenous communities demanded his return, and in 2014, after the sequencing was complete, the Anzick child was finally reburied.

The ochre returned to earth, the bones sealed once more beneath the soil of Montana.

But the data — the story — lives on.

Today, Anzick-1 remains the only human from the Clovis culture ever found.

No other skeleton, no other DNA, has survived from that era.

His tiny frame is the sole biological voice of a civilization that once spanned a continent.

From the icy plains of Alaska to the deserts of Mexico, over ten thousand Clovis spear points lie scattered — each one a frozen heartbeat from a vanished world.

But only one body remains.

Only one child tells their story.

And his story is not over.

As technology evolves, scientists are beginning to glimpse what lies beneath the myth of “Clovis First.”

Sites like Monte Verde in Chile — older than Clovis — and the 23,000-year-old footprints of White Sands, New Mexico, whisper of even deeper roots, older wanderers who walked the Americas before the ice

began to melt.

Anzick’s genome doesn’t end the mystery — it opens a door to an even older one.

Somewhere under layers of soil and centuries of silence, more ancestors wait.

Their DNA may already be dust, or it may still hum quietly in a forgotten tooth, a buried bone, a grain of ochre.

And when those stories finally rise, they may tell us not just who the first Americans were — but who we are when the earth remembers.

Anzick-1’s short life ended twelve millennia ago, but his legacy endures in every heartbeat of his descendants.

His genome — three billion letters long — is the oldest full human story of the Americas.

It tells of a people who crossed frozen oceans, buried their children in color and love, and left behind tools sharp enough to pierce time itself.

In the end, the boy from Montana did not vanish.

He was found — and through him, so were we.