Experts Just Found a SECRET CODE Hidden in Da Vinci’s Last Supper — And It Changes Everything You Thought You Knew!

Experts Just Found a SECRET CODE Hidden in Da Vinci’s Last Supper — And It Changes Everything You Thought You Knew!

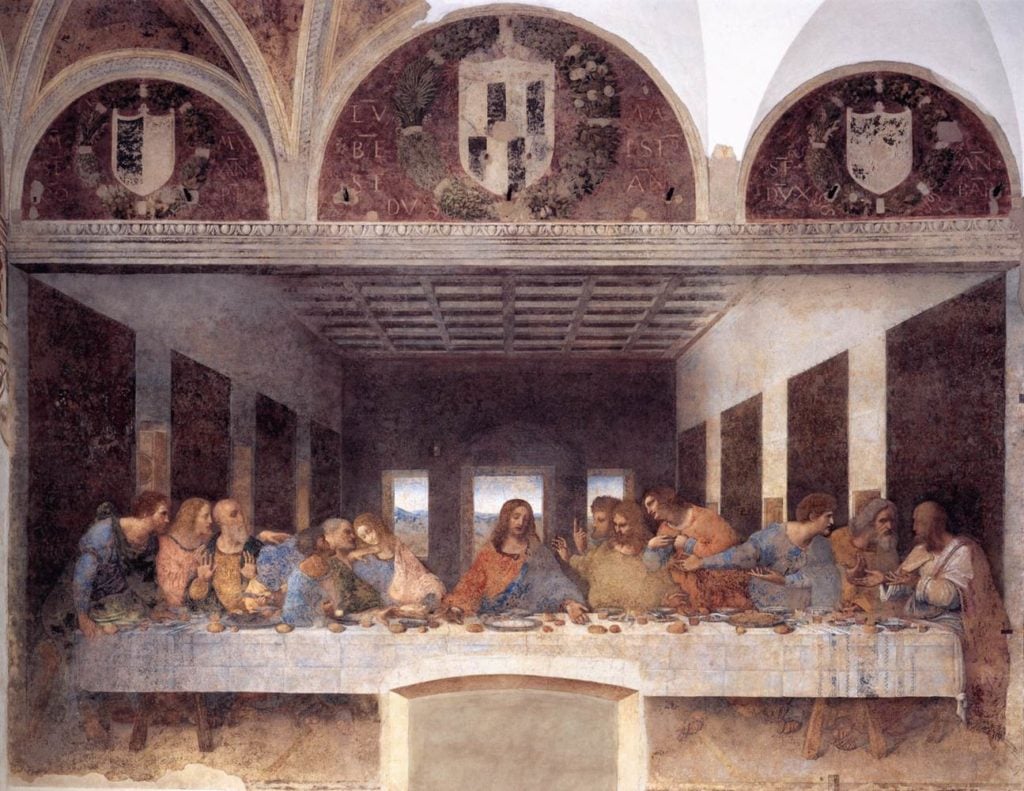

For more than five hundred years, The Last Supper has watched silently from the refectory wall of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

Painted between 1495 and 1498, Leonardo’s depiction of Jesus and his twelve apostles during their final meal has been endlessly analyzed, copied, and mythologized.

Yet, for all its fame, the painting remains an enigma — a visual riddle left by one of history’s most brilliant and secretive minds.

At first glance, it’s a simple biblical scene: Jesus, calm and luminous at the center, has just told his disciples that one of them will betray him.

Shock ripples through the table.

James throws his arms up in outrage; Thomas points a questioning finger; Philip bows in disbelief.

Even the salt cellar before Judas — the betrayer — has toppled, as though the painting itself recoiled from his treachery.

And yet, among the chaos of emotion, one figure breaks every rule of expectation — the delicate, almost ethereal person seated to Jesus’s right.

Traditionally, this figure is said to be John — the youngest apostle.

But many have noticed something unsettling: the figure looks distinctly feminine.

Smooth face.

Flowing hair.

A tender, almost intimate lean toward Jesus.

And when you see it, you can’t unsee it.

For centuries, whispers have suggested that this is not John at all — but Mary Magdalene.

If that’s true, the implications are staggering.

Early Christian texts, long suppressed or lost, often hint that Mary Magdalene was far more than a repentant sinner.

The Gospel of Mary, a 2nd-century manuscript discovered in Egypt, portrays her as Jesus’s closest confidante — wiser and more insightful than the male apostles who resented her.

Another, the Gospel of Philip, calls her Jesus’s “companion” — a term many scholars interpret as wife.

It even mentions that Jesus “used to kiss her often on…” the rest of the line lost to time and damage, though most assume the missing word is “mouth.”

Now, when you return to The Last Supper, you can’t help but see it differently.

Look closely between Jesus and the supposed John.

Their bodies form a sharp, open V — a shape many interpret as the symbol of the feminine womb.

A deliberate gesture, a whisper of divine union.

But if you connect the outlines of Jesus and this mysterious companion, the “V” transforms into an “M” — a possible nod to Matrimony.

Was Leonardo hinting that Jesus and Mary were wed — and that their secret lineage lived on?

To believers, that’s heresy.

To Da Vinci, perhaps, it was truth wrapped in geometry.

But this theory — popularized by The Da Vinci Code — was only the beginning.

A Serbian information technologist named Slavisa Pešić claimed to uncover a deeper secret hidden in the painting’s very structure.

By overlaying The Last Supper with its mirrored reflection, Pešić said he discovered new, ghostly figures emerging from the symmetry: two armored knights resembling the fabled Templars, a woman cradling a

child, and — before Jesus — a chalice glowing faintly from the overlap.

If true, the implications were explosive.

The Templars were rumored to have guarded the Holy Grail — not merely a cup, but a bloodline.

Was Leonardo hinting that the Grail wasn’t a vessel at all… but a person? Perhaps the child of Jesus and Mary Magdalene — hidden in plain sight, buried within brushstrokes that only a mirror could reveal.

When Pešić published his findings, the internet nearly imploded.

Da Vinci forums crashed under the frenzy.

Some hailed it as “the discovery of the century.

” Others called it blasphemy, or worse, delusion — pareidolia, the human tendency to see patterns where none exist.

But even as critics dismissed it, the coincidences piled up.

Then came the numbers.

Skeptics who studied the painting’s composition began noticing a strange symmetry — a numeric code woven into the placement of the apostles.

On each side of Jesus: two groups of three figures.

Add Jesus in the center, and you get 3-3-1-3-3 — a pattern that some claimed Da Vinci used intentionally.

But why?

One theory traced the code to Lamentations 3:31–33, which reads: “For no one is cast off from the Lord forever… though He brings grief, He will show compassion.

” On the surface, it’s biblical comfort.

But historians pointed to something more personal — a hidden confession.

In 1476, a young Leonardo da Vinci was arrested and charged with sodomy, a crime punishable by death in Renaissance Florence.

Though the case was dropped, the accusation haunted him for life.

Could the pattern “33133” have been his private plea — a mathematical cry for forgiveness? A way of encoding his truth into sacred art, daring the Church to see without ever realizing what it saw?

But Leonardo was not a man of single meanings.

He painted in layers — physics, theology, anatomy, and mathematics merging like gears in a celestial machine.

In 2007, an Italian computer specialist named Giovanni Maria Pala claimed to have uncovered a musical score hidden in The Last Supper.

By drawing lines across the apostles’ hands and loaves of bread, he found a pattern resembling musical notation.

When transcribed and played backward — the direction of reading in Da Vinci’s time — the notes formed a haunting 40-second melody.

A soundtrack to betrayal.

Low, solemn tones that rose and fell like a heartbeat — eerily human, eerily divine.

It wasn’t beautiful, but it was deliberate.

And for those who believe in Da Vinci’s genius, it was undeniable proof that the master had composed more than just a painting — he had written a hymn.

Yet even that wasn’t the final twist.

In 2010, Vatican scholar Sabrina Sforza Galitzia announced a discovery that reignited global fascination: Da Vinci’s masterpiece, she said, contained an astrological prophecy.

Using the window above Jesus — the half-moon that floods the center of the mural with light — she decoded what she described as a celestial timeline embedded within the architecture.

According to her calculations, Da Vinci had predicted a cataclysmic flood that would begin on March 21, 4006, and end on November 1, 4006.

A symbolic end of humanity — followed by renewal.

The claim was ridiculed, of course.

But even skeptics had to admit: Da Vinci’s obsession with astronomy, cycles, and the divine proportions of the cosmos made the idea plausible.

He saw time as geometry — the world as a series of repeating equations.

Could he have encoded his vision of humanity’s end not as a prophecy, but as a warning?

Five hundred years later, his masterpiece still refuses to stay silent.

Each generation finds something new: a cipher, a melody, a message.

Perhaps Da Vinci intended it that way — to ensure that the painting would live forever in question, never in certainty.

Maybe The Last Supper isn’t hiding a single secret at all.

Maybe it’s a mirror — reflecting whatever mystery humanity needs most at the time.

A love story.

A confession.

A code.

A prophecy.

And maybe that’s the true genius of Leonardo da Vinci: he didn’t just paint a moment in time.

He painted an eternal puzzle — one that watches us as much as we watch it, waiting for someone brave enough to finally understand what he was trying to say.

And when that moment comes, perhaps the real “Da Vinci Code” will not be found in paint or pigment, but in us — the very people still searching for meaning in his silence.