Track 61: The Underground Passageway for Celebrities and Presidents at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel! What Lies Beneath?

New York City has always been a hub of innovation and ambition, particularly when it comes to its transportation infrastructure.

By the mid-19th century, railroads had already begun to shape the city, though not without causing chaos at street level.

Freight yards cluttered the surface, creating a tangled mess where coal, cattle, and commuters collided.

However, in 1844, the Long Island Railroad took a bold step by constructing the Atlantic Avenue tunnel, the first subterranean rail tunnel in North America.

This groundbreaking achievement demonstrated that New York’s railways could indeed delve beneath the chaos of city life, paving the way for a new era of underground transit.

Fast forward to 1910, and the landscape of New York was undergoing a dramatic transformation.

Tunnels crisscrossed the city, and the Pennsylvania Railroad had taken the concept of underground travel to new heights by constructing a fully underground terminal on 7th Avenue.

This innovative infrastructure allowed mailbags to rise directly from trains to sorting floors without ever touching the street, revolutionizing the way goods and services moved through the city.

The meticulous engineering of these tunnels created a hidden world beneath the bustling streets, a world that few had the chance to see.

The New York Central Railroad, seizing upon the momentum of this underground revolution, electrified its entire system following a tragic locomotive collision in 1902.

When Grand Central Terminal opened its doors in 1913, it quickly became one of the busiest railroad terminals in the world, handling close to 75 million passengers annually.

The terminal’s design was a marvel of engineering, featuring two levels of platforms and storage yards that extended from 42nd Street to 50th, with tracks running beneath Park Avenue all the way to 96th Street.

Above ground, the city flourished with hotels, offices, and towering skyscrapers, all built atop the intricate web of tracks below.

Among these subterranean marvels was the Lexington Yard, known colloquially as the Lexard, nestled beneath the east side of Grand Central between 42nd and 50th Streets.

This was where coal trains once rolled in to fuel the steam powerhouse on 49th Street, supplying heat and electricity to Grand Central and its surrounding buildings.

The ash generated from this operation was carted out through wide platforms situated between tracks 61 and 63—a curious detail, as there was no track 62.

The atmosphere in this underground realm was gritty and industrial, filled with the sounds of rumbling ash carts and the smell of steam and oil wafting through the air.

It was a hidden labor force that kept the grandeur of the city above running smoothly, yet few ever laid eyes on it.

Everything changed in 1929 when the powerhouse was demolished to make way for the luxurious Waldorf Astoria Hotel, then the most opulent building in New York City.

As the Waldorf rose, Track 61 lost its original purpose, but little did anyone know that it was about to gain a new and intriguing identity.

The block between Lexington and Park, 49th to 50th, was prime real estate, and when the railroad’s power block at 49th Street came down, the tracks had to remain operational beneath the new hotel.

The New York Times reported on September 8, 1929, that the hotel corporation secured a 63-year lease over the tracks, which included a private rail siding and a special elevator for arrivals.

Construction of the Waldorf moved quickly, and by 1931, the hotel was officially open, standing 47 stories tall and spanning an entire city block.

It soon became a symbol of high society, hosting glamorous events and attracting the elite of New York and beyond.

The Waldorf Towers, perched at the top of the hotel, offered luxurious long-term apartments for heads of state, moguls, and cultural icons.

Among its famous residents were composer Cole Porter, who lived there for over 20 years, and General Douglas MacArthur, who returned from service in Asia to stay at the Waldorf.

As the hotel became a hub for society’s elite, the arrival process took on a new level of significance.

For the average businessman or well-to-do tourist, entering through the grand lobby sufficed.

However, for those at the top of the social hierarchy, arriving in a private vehicle or even a private train car was the ultimate statement.

The Waldorf was equipped with its own private garage, a rarity at the time, allowing cars to be shuttled directly to the service core and freight elevators, bypassing the public eye entirely.

This was not just about luxury; it was about security and status.

Beyond the public spaces of the hotel, hidden service corridors led to an unmarked door on 49th Street, which opened into a freight elevator large enough to accommodate automobiles.

This elevator descended two stories to a platform nestled between tracks 61 and 63, originally designed to move coal and ash.

With the hotel’s opening, this space was transformed into a private train stop, allowing guests arriving by rail car to step directly into the hotel’s back house, unseen by the public.

The elevator, installed during the hotel’s construction, opened onto 49th Street, providing a discreet entry point into the bustling hotel above.

The first documented arrival at Track 61 occurred in April 1938 when General John J.

Pershing, the only man to hold the rank of general of the armies, disembarked from a private rail car and took the elevator directly into the Waldorf.

However, the most famous visit came on October 21, 1944, when President Franklin D.

Roosevelt used the sighting while campaigning in New York.

This visit solidified Track 61’s place in history, as it was documented by the Secret Service and reported in the media.

Over the years, other notable figures, including General Douglas MacArthur and even dignitaries during the UN General Assembly, utilized this hidden passageway.

Despite its storied past, much of Track 61’s allure comes from the legends and myths that have grown around it.

Former railroad employees spread tales of Roosevelt’s bulletproof limousine being rolled off a train and driven directly into the hotel via the freight elevator.

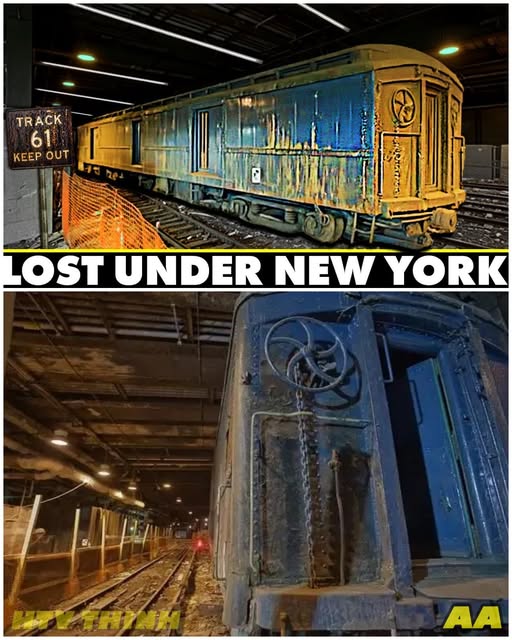

This narrative gained traction, further fueled by urban explorers and tour guides who claimed to have seen Roosevelt’s secret train car waiting in the shadows.

However, investigations revealed that the blue baggage car often associated with these stories was not Roosevelt’s at all, but rather a standard baggage car used for transporting equipment.

Today, Track 61 remains sealed off from the public, its tunnel mouth visible from certain Metro North trains, but the platform itself is locked and used only for maintenance.

Despite its dormancy, it still holds strategic value, listed in security planning documents as a potential evacuation route for heads of state.

The intrigue surrounding Track 61 continues to captivate the public imagination, standing as a testament to a bygone era when rail and hospitality intersected in a unique and fascinating way.

In conclusion, Track 61 may not be the glamorous stage for spectacles that many imagine, but its history is rich with stories of power, secrecy, and urban legend.

As urban explorers, journalists, and tour guides continue to weave tales of hidden cars and presidential convoys, the platform remains a symbol of New York’s enduring fascination with its hidden tunnels and the

secrets they hold.

The truth may be less glamorous than the myths, but it is no less compelling—a reminder that even in the heart of one of the world’s busiest cities, there are stories waiting to be uncovered beneath the surface.